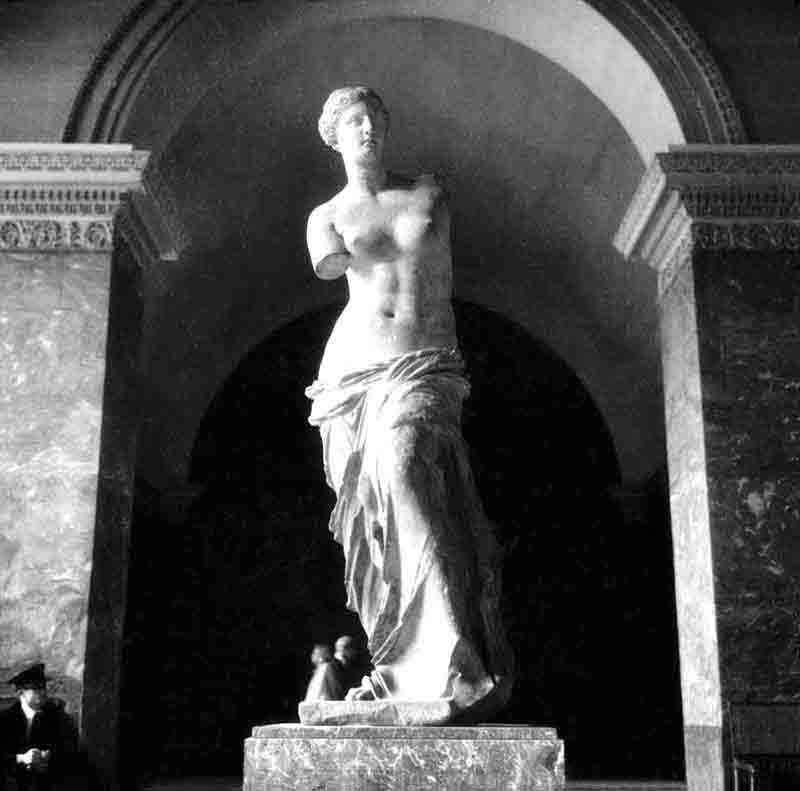

The Venus de Milo has become an unrivalled international icon although she has no arms, or maybe precisely for that reason. She is the most notable and universally known Venus statue. Created between 130 and 100 BC, the statue is believed to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty. Her great fame is due not only to her beauty, but also to a great publicity campaign by the French authorities in the nineteenth century.

Goddess of love and female beauty

One of the most prominent sculptures in the history of art, she continues to fascinate the visitors in the Paris Louvre to the present day.

The Venus de Milo symbolises the ideal of beauty of her time

One of the most prominent sculptures in the history of art, she continues to fascinate art collectors around the world and the visitors in the Paris Louvre to the present day.

Two hundred years ago this masterpiece of Greek antiquity was found by a farmer in a field.

She has been considered an icon of sensual female beauty since the antique. The story of the rediscovery of the goddess of love is as mysterious as its original content

Where was the Venus de Milo discovered

Early April 1820: On the small Aegean Sea island of Melos - new spelling Milos; then part of the Ottoman Empire - the Greek farmer Georgios Kentrotas is searching for quarry stones for building houses.

He unexpectedly comes across a chunk of marble on a mountain slope. Initially he hardly takes notice of the finding, as the forms are too round for building a wall.

The outstanding importance of his discovery is not obvious to him.

French naval officer Olivier Voutier claimed in his memoirs that he was in the area on the day of the discovery and offered Kentrotas 400 piasters ( over a month's salary) for his discovery.

Since he did not have enough cash with him, he reported to his superiors.

The news reached the French ambassador in Constantinople, Charles François de Riffardeau Marquis de Riviere, who ordered his secretary Comte de Marcellus to travel to Milos to purchase the statue.

Preparations for the journey took time, and de Marcellus did not reach Milos until May 23, 1820, but by that time Turkish sailors were already busy loading something "big, white and heavy" onto one of their ships.

As a result, a fierce argument broke out between French and Turks over the statue. The speculation that the arms and hands of Venus were lost in the fight, as some later reported, is part of the speculation and most likely not true.

Represented by the crescent moon and the Venus symbol is the Goddess Tanit

The statue was made of two blocks of marble, the upper body and the lower draped legs and an inscribed base. "She reached for her clothes with her right hand, which covered her only up to her hips and dropped to the floor with wide folds.

The one on the left was slightly raised and bowed - in it she held a ball the size of an apple," Kentrotas is supposed to have described his find.

The emissary de Marcellus finally presented the Turkish captain with a preliminary sales contract.

After tenacious, two-day negotiations - including a bribe - he was able to take ownership of the Venus for France.

The mayor of Milos, Gerasimos Damoulakis, however, later said that the statue had been stolen from the Ottomans by a French officer and then loaded onto the warship "L'Estafette".

Another version of the events is that the arms and hands as well as the original pedestal were apparently still there at the beginning and were only lost during the shipment of the work to Paris.

Experts had in fact ascertained from the patina (oxide layer) on the fragments of the hands that they must have been discarded a long time before the statue was found.

Today, it is no longer possible to prove which of these stories is the truth.

Goddess of love and beauty

The slightly larger-than-life, with a height of 203 cm, half-naked statue is supposed to represent the Venus of Milo, the Roman pendant of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and female beauty.

Her figure is a blend of Indo-Germanic-Hellenic, Aegean-Little Asian and Semitic-Oriental elements.

In Homer's work she is the daughter of Zeus and Dione, an ancient Indo-Germanic sky goddess. " For Homer, " she is the mistress of the chariots.

She is tender and unwarlike. Grace, beauty and seduction are associated with her.

According to some scholars, though, she is the sea goddess Amphitrite, who was worshipped on Melos. Others believe that they identify her as the goddess of victory, Victoria.

The marble female figure is one of the most renowned works of Hellenistic art. It was presumably created by the sculptor Alexandros of Antioch between 130 and 100 BC.

She symbolises the ideal of beauty of her time, with small breasts and a well-formed pelvis. She is tender and unwarlike, grace and seduction are associated with her.

Her enigmatic body rotation is particularly striking: her robe is slipping away, her upper body and hips are already naked.

An S-curve runs through the whole figure, the upper part is slightly bent back.

The scene could represent Aphrodite after the bath, preparing for the Paris Judgement, with outstretched arms holding an apple in her palm.

In its original state, the sculpture would have been tinted with color pigments to create a more natural look, which would then have been decorated with bracelet, earrings and headband before being placed in a temple.

Nowadays there are no traces of dye and the only signs of metal jewels are the fixing points.

Below her right breast is a filled cavity that originally contained a metal pin which would have held the separately carved right arm.

The Golden Apple of Discord

In this narrative, the young Trojan prince Paris received a golden apple from the goddess of discord, with which he was to award the most beautiful of the three candidates: Aphrodite, Athena and Hera.

Aphrodite won the beauty contest by bribing Paris with the passion of the most beautiful mortal woman - Helen of Sparta - and was awarded the apple.

The missing hands, meanwhile, also suggest other interpretations: Due to the rotation of the shoulders and torso, Venus once held a thread with one hand and a spindle in the other.

It is also speculated that she held the shield of Mars, the god of war, a bow, a spear, an amphora or a belt in her hands.

There are even speculations that she was part of a sculptural ensemble. But there is no proof for all these theories.

Napoleon's aftermath on the art world

In the beginning of the 19th century the french art world was in turmoil. The Louvre was in need of new classical works of art. When Napoleon finally lost his throne in 1815, looted art had be returned to its owners.

“Laocoon and his sons” and the “Apollo Belvedere” were returned to the Vatican, the Italians were reunited with the “Venus de Medici.”

Faced with this loss, the French felt compelled to promote the Venus de Milo as a greater treasure than the one they had recently lost.

The cover up starts with a missing piece

The Venus de Milo was found to have been carved from at least six or seven blocks of Parian marble; one block for the nude torso, another block for the draped legs, another block apiece for each arm, another small block for the left foot, another block for the inscribed plinth, and finally, the separately carved herm that stood beside the statue.

When it was introduced into the Louvre in 1821, the museum dated the creation of the Venus de Milo in the classical period, which was the most desirable artistic period.

Based on early drawings, the plinth was known to have the dates 130 to 100 BC on it. The inscription read: (Alex)andros son of Menides, citizen of Antioch on the Maeander made this statue.

The inscription dated the statue to the Hellenistic period, because of the style of lettering and the mention of the ancient city of Antioch on the Maeander.

In the early to mid 19th hundreds the Hellenistic Age was considered a period of decline for Greek art.

Initially it was determined that the pedestal fitted perfectly as part of the statue, but after its inscription was translated and dated, the embarrassed experts who had publicly acknowledged the statue as a work of the classical period, rejected the pedestal as a potential later addition.

The quality workmanship in the carving would not have fit into the incorrect assessment of Hellenistic art, the experts argued and the plinth was broken off and mysteriously disappeared shortly before the statue was presented to King Louis XVIII in 1821.

The king, who was not enthusiastic about the armless beauty, decided to hand over the statue to the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Riddles and Temptation of the Venus de Milo

Reproduced collectibles - smaller, affordable versions of the famous discovery of the Venus statue, were popular in the 1840s and 1850s.

They were collected especially by the bourgeoisie to express their knowledge and good taste.

The young photo enthusiast John Beasley Greene, who had learned the craft from Gustave Le Gray, one of the first accomplished french photo artists, purchased a miniature plaster copy of the Venus of Milo and placed it on his Parisian roof.

This was the beginning of photography in the context of art reproduction.

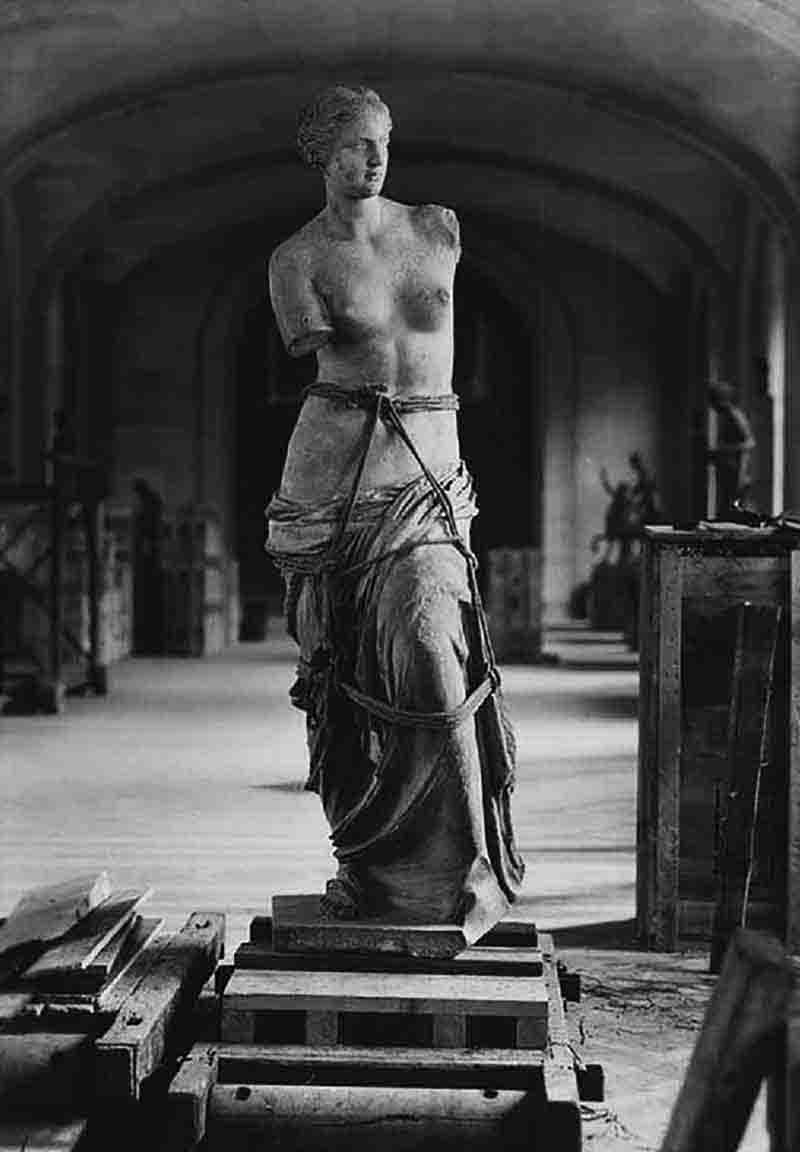

Saving the Venus de Milo

In 1871, during the Paris Commune uprising, the Venus de Milo statue was taken from the Louvre Museum in an oak box and hidden in the basement of the police headquarters. Although the prefecture was destroyed by fire, the statue survived undamaged.

In autumn 1939 she was once again evacuated from the Louvre, and hidden in Château de Valençay from potential looting.

Ten days before Hitler's invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, two hundred trucks carried treasures out of the Museum, including the Venus de Milo.

The most important art rescue operation ever was organized by Jacques Jaujard, the director of the Louvre.

A plaster copy of the Sculpture was installed in the Louvre to conceal the absence of the original.

Jaujard continued to work in the Louvre during the occupation and had to withstand not one, but two adversaries.

One was the occupying troops, led by greedy art looters. The other was his own superiors, part of a collaborating administration.

However, the helping hand he received was dressed in a Nazi uniform, Count Franz Wolff-Metternich, in charge of art protection, the "Kunstschutzeinheit".

An art historian and Renaissance specialist, Metternich was neither a fanatic nor a member of the National Socialist Party.

He knew where all of the museum's works of art was hidden since he had personally inspected some of the repositories.

Yet he assured Jaujard he would do everything to keep them safe from German army raids.

Goebbels requested that all works of art from French museums be shipped to Berlin. Metternich then argued that this would be possible, although it would be advisable to postpone this until after the war.

Metternich saved the Louvre by sabotaging the Nazis' looting machine. The art treasures would certainly have been destroyed during the bombing of Berlin

After the war, Metternich was given the Légion d’Honneur by Géneral de Gaulle. It was for having “protected our art treasures from the appetite of the Nazis, and Göring in particular.

The darling of the Louvre

It was not until 1951 that the museum gave the correct dates of the Venus of Milo's creation. Her unique fame is therefore partly the result of the intentionally misguiding branding campaign of the Louvre, which was intended to restore France as a leading art nation and make the Venus de Milo the most popular of all Venus Statues.

The Venus de Milo remains one of the most beloved attractions of the Louvre in Paris.

Are you curious about music, art, technology, fashion, humanity, lifestyle, and beer?

If so, then you need to subscribe to the free Likewolf newsletter.

100% privacy. When you sign up, we'll keep you posted.

The Journey Continues

Explore the Next Chapter Today